I will keep with the Japanese convention of Family name first, thus, KIMURA Kazuo. Also you will see KIMURA san, with san, meaning roughly, Mr. Since we are mainly talking about Japanese people, why not. Some names may not be correct, even for native Japanese (who has helped with the name translations for me), deciphering names is problematical, as there is a myriad of different ways in which these names could be written in Kanji and sometimes they can be very esoteric.

KIMURA Kazuo, the designer credited with the exterior of the Silvia, was born in the Higashi district of Osaka, in July 1934. After finishing his schooling, he studied at the Asagaya art Institute of Tokyo for a year. From there KIMURA san went onto Tokyo Geidai University, Faculty of Art and Crafts Department. This faculty was the starting ground for a lot of young designers who went to work for the various automotive companies in Japan. In the same (scholastic) year, people like INOGUCHI Yoshimi (ISUZU Bellett fame), along with NAITO Hisamitsu and also SATO Masahiro (both the legendary Bellett 108), KATAYANAGI Shigeaki (Prince) and SAWADA Katsuhiko of KANTO JIKOU. The previous year there were: NOZAKI Saturo (of Toyota 2000GT fame), KAWAMURA Masao and MORI Taisuke (both of Honda S fame), SASAKI Touru of Suzuki, NOZAKA Teizou of Toyota Car Body and KAJIWARA Hidetoshi of Nissan. Even though KIMURA san’s graduation project was train orientated, KIMURA san received an invitation to join Nissan (in 1958) from SATO Shouzou, head of the design moulding section. This invitation from SATO san was one of the main reasons KIMURA sans joined the company.

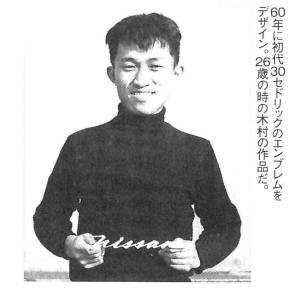

KIMURA sans first task was the design of the emblem of the 680, which was a large truck. In 1959 as design assistant under SATO san, he helped design the Bluebird wagon (model code WP311). It is worth pointing out before we go much farther, that the Datsun Bluebird series was the original ancestor of the 311 chassis lineage, which would give us later the CSP311, SP311 and the SR311 models. But its DNA can be linked back previous models with chassis codes of 211 and the 110, which was launched in January 1955.

His next task in May 1959 was to design the radiator grille for the Datsun 222, followed by sketching the instrument panel for the 312 Bluebird in October of the same year. Also (un-sure of timescale) KIMURA san was involved in modelling of the A48X project, a sedan car that would be able to travel over Japan’s rough roads and have an excellent running ability on par with European cars. Again for this project he was under SATO san, who was in charge of design, with TEIICHI Hara as project manager. Also involved was SHUZO Uneno, IDA Isamu and TAKESHI Hiroshi. An innovative horizontally opposed OHV engine was fitted to the A48X, and become project A49X, under manager FUJITA Shojiro. At some point in late 1959 SATO san left and was replaced by YOTSUMOTO Kazumi as head of the design moulding section.

After that, KIMURA san designed the emblems for the Cedric 30 (1960). The next project was the A260X, a small compact car, designed by KAJIWARA Hidetoshi in February 1961. A prototype was fabricated, with KIMURA sans help on the instrument gauges and interior. But this first compact car for Nissan stopped here, as KAWAMATA Katsuji, Nissan President, had no interest in a small car, and the cost in setting up for mass production killed the prototype off.

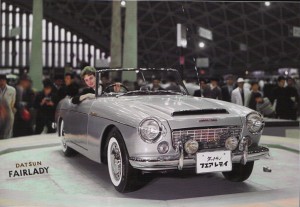

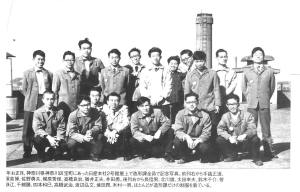

Also within the Nissan design team was IIZUKA Hidehiro, who started work on a new sports car in 1958. This was the Fairlady 1500 (model code SP310) and a running prototype was unveiled at the 8th Tokyo Motor Show 25th Oct- 7th November 1961 (image below). During the time after this show, small design and styling changes were made, e.g. the addition of quarter light vent windows and a soft top were added before its release to the general public in October 1962.

People from the image above;

From the right to left, front row, TESEN Masamichi, IIZUKA Hidehiro, SAN0 Isao, KAJIWARA Hidetoshi, TAKAHASHI Yoshiharu, TARUI Aki and IDA Isamu.

From right to left, rear row, NAGA Nobuo, KITAGAWA Yu, OOTA Yukio, SUZUKI Sensuke, KANNO Shizue (note-female), CHIWATA Masaru, YOTSUMOTO Kazumi, TAKAHASHI Takeharu, WATANABE Hirobumi, SAKAIDA Jun and KIMURA Kazuo. Most of them are wearing “Creative Section’s only uniform”.

Now a slight step back in years to bring another player of the Silvia development to the table, Yamaha. Yamaha successfully joined the booming motorcycle industry in Japan, and in about 1958 started working on micro cars that fitted into the newly formed K-class of cars. This popular class was a Japanese government formed class of engine size of 360cc or less, which had very lenient tax and licensing requirements. But this market was soon swamped by rivals and Yamaha bowed out, but decided to look for a niche of its own.

With that niche in mind, ONO Shun and YASUKAWA Tsutomu set up the Yamaha Technology Institute and in September 1959 went on a grand tour of American and European car manufacturers to seek knowledge and inspiration. They noticed that sports and GT constructors mostly still worked on a one-by-one basis, by hand, rather than the mass production way. At that time, Japan still lacked the huge resources and facilities to mass produce, and YASUKAWA and ONO san thought about the higher power, lower production area of car production for the discerning enthusiast. On their return to Japan in November, they set up the Yasukawa Institute, aiming at high performance sports cars. Soon the Institute had purchased a MGA twin cam from a US Occupation Forces army officer (as officially unable to buy foreign made vehicles) and a Facel-Vega Facelia, another DOHC powered car. These were tested and dismantled to gain knowledge and understanding. Ironically both of these engines were withdrawn from the market by their manufacturers due to serious reliability problems. Maybe from that, Yamaha created a robust and efficient 1.6Litre DOHC of their own.

Now for Yamaha, the next step was a car for the engine to go in. This would be the two YX30 prototypes. The first, a small convertible sports car, styled by GK design (headed by Professor KOIKE from Tokyo Art University), completed in November 1960. The second was a closed 2+2 body finished in June 1961. Whilst these two projects were running, Yamaha was investigating and developing a 2.0 Litre, 4 cylinder DOHC engine, code-named YX80.

But a serious slump in scooter and motorcycle sales in Japan made Yamaha cut its costs, and the engine would be shelved and both Yamaha Institutes were broken up. This slump caused Yamaha financial difficulties and this is probably the cause for Nissan and Yamaha being entered into an imposed partnership, by a mutual financing bank in 1962. The Yasukawa Institute was restarted, but its purpose changed from doing its own designs, to now facilitating development and testing systems for its new partner. This included a soft top for the Fairlady 1500 and its battery location. Next Nissan asked if the shelved YX80 engine could be adapted to fit the Nissan Cedric. This project was mainly a revenge driven exercise, as Toyota had trounced Nissan at the 1st Japan GP (May 1963) with their win in class, Nissan wanted to return the success at next year’s GP. But this never came to fruition.

Development began in October 1962 for a 2 Litre successor to Nissan’s Fairlady 1500. At the same time, the 9th Tokyo Motor Show was being held; Hino displayed its Contessa 900 Sprint. This was designed by Giovanni Michelotti; one of Italy’s legendary styling designers. The young designers at Nissan were inspired to produce something themselves to be shown at next year’s show.

The successor to the Fairlady had an original request to have a steel monocoque body with separate sub-frames, long nose and fastback rear, retractable headlights, four wheel disc brakes, curved side glass and a 2 litre engine (YX80). Design on this and a request for a sporty closed coupe on the Fairlady platform (Datsun 1500 coupé-CSP310) started. The 2 litre project was assigned the development code A550X.

What about the development code for the coupé that would become the Silvia? According to Kimura san it never got a development code, as the design was started without permission by the car design department.

So far little information on the early timeline work on both of these projects has come to light. With the A550X project, which was started first, enough of a design was in place from KIMURA san and others from Nissan, so that Yamaha could start the design implementation. KIMURA san was also drawing sketches for the closed coupé with the aid of YOSHIDA Fumio (sometimes wrongly translated as Akio), who concentrated on the interior and HISATERU Ogura who was assistant to both.

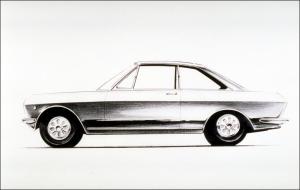

The important sketches for what would be known as the Silvia are from March 1963 (below) showing something much more resembling the final design. The rear view of these sketches is identical to the finished prototype and production model (apart from having smaller rear lights). KIMURA san also really wanted to tackle the challenge of incorporating retractable headlights (also visible from the sketches) which were part of the broader request. Eventually, though, they settled on four fixed round lights, because the retractable form was proving difficult to get right and would not have passed American safety standards. Not that this was a main concern looking at potential export markets, this was after all a prototype where many concepts and ideas come to the table and fall by the wayside. But the design had to look at incorporating them now to fit in the whole design rather than an afterthought. The sketch shows a fastback, which was part of the original design brief. Though the angle of the `C’ pillars would later change. Kimura san says he had a hard time modeling the body side and C pillar of the design that flows from the fender to the body side and C pillar.

“The shape of the front grille was decided in one day, and the design instruction drawing was compiled in one hour. Since the license plate does not fit well on the top and bottom of the rear bumper, I (Kimura san) divided it into two and put the number light in the cut bumper”. By May 1963 the design of the CSP310 was almost complete.

Nissan hired Albrecht Goertz as a design consultant on a one year contract, arriving in May 1963 on one of his 5 or 6 fortnightly visits throughout his contract year.

To get a fuller overview of how Mr Goertz’s small involvement in the CSP311 development came about, we have to step back to 1960, when SATO Shouzou, who was head of the Styling Section for a long time, resigned. At that time within the Styling Section of Nissan, they had no one of sufficient ability to take Sato san’s place. Nissan top management were quite worried and had to see about out-sourcing their new vehicle design. This is why Pininfarina designed the next version of the Datsun Bluebird (released for sale in September 1963).

Also, about the same time, Nissan were introduced to a USA company based in Detroit, called Creative Industry, who provided clay models for new vehicle designs. These clay models were full size master models, and from these, molds could be taken from them for production purposes. So, Nissan decided to try this technology for the Pininfarina designed Datsun Bluebird.

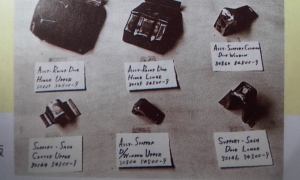

But, Nissan had two hurdles to overcome. Firstly, Nissan used clay made from wooden wax, widely found in candles used in shrines and temples. This hard wax was difficult to model with. From the contact with Creative Industry, Nissan could see the modelling wax used by the USA automotive industry, supplied by the Chavant company. The Chavant modelling clay is made from bees wax, dark red in colour and easily worked with at 40°C.

The second hurdle to overcome was the fact the clay modelling done within Nissan’s Styling Section was only done with quarter scale models and full size vehicle body drawings. The drawing would be used further in the engineering and design to check for space and strength for the handmade testing vehicles.

Nissan set up a new Section, the Model Making Section, Trial Manufacturing Department, who successfully used full size clay models to help produce the new Bluebird model. Nissan realized it had a future problem as the Styling Section did not know about the full size clay modelling method. This problem was solved by hiring Mr Goertz to teach the Styling Section how to approach full scale modelling.

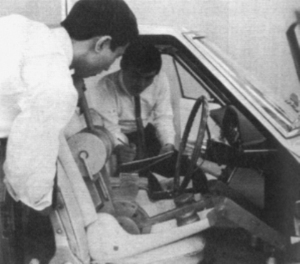

According to NAGATA Shigeru, a Nissan employee who was assigned as Mr Goertz translator, saw how he helped transform Kimura sans design of the CSP310 into a full scale model and give good advice on clay modelling as a whole. The full scale model of the CSP310 was put into a large room at Mr Goertz’s request, where the actual clay design could be checked from various angles. Mr Goertz asked to make necessary changes to the model as part of the styling design for the project. Mr Goertz also changed Nissan’s use of small hand tools for the clay modelling, showing his own, and having new ones made for the job of now full scale modelling. Up to this point, clay modelling was not an established job, so Nissan changed that by employing people for this new role.

Sharp designs were all the rage in Europe as with the trend of the likes of Bertone, Ghia and Michelotti. KIMURA and his colleagues were taken by the Contessa, as well as having a greater understanding of the style during that period, they wanted to do something themselves. With the probable additional aid of Mr Goertz the final design of the CSP310 was sharpened up, became more mature and paid consideration to productivity concerns. The main change Mr Goertz added to KIMURA san’s design was changing the angle of the “C” pillar, though the line of the front pillar, roof and behind was also a concern of the design team. YOTSUMOTO Kazumi (No.3 Design Planning Dept. – concerned with overall body design) feels that they were getting close to where they wanted to at the production model. He also says the Fairlady had a good layout and a good starting point for the CSP310 and he tried to consider in which direction the car would go for styling, driving and the future of the style.

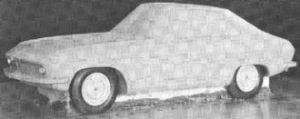

Also a consideration early on in the cars inception was to reduce air resistance. Wind tunnel work was carried out on early forms of the car (prototypes) but not the commercially released model, though the production model changed little from the prototypes. IZUMI Tomoharu (No.1 Design Planning Dept. – 1st body design section) points out that in general most passenger cars have a drag coefficient of between 0.5 and 0.7, though the Silvia got down to a coefficient 0.45, which was un-usual for the time. AOKI Hideo, a test driver, adds the car design was not governed by factors such as having a lower drag coefficient.

The CSP310 prototype was scheduled to debut at the 1963 10th Tokyo Motor Show, so ranked a higher priority than the already started A550X project. Thus, in May, Yamaha stopped their work on the A550X project, and concentrated on taking measurements and hard-points for the re-bodied Fairlady concept. By June 1963, Nissan had supplied drawings of the coupe body and Yamaha could start building the wooden bucks so the body panels could be formed.

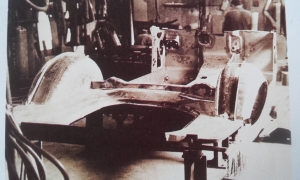

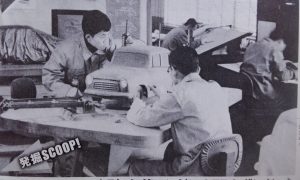

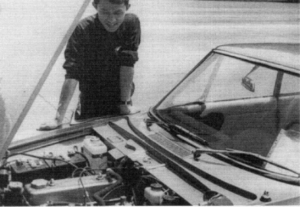

Kimura san asked Yamaha to make a 1/1 wooden model with a 1/4 clay model and a design drawing. Kimura san visited Yamaha once every two weeks. He also asks Yamaha to disassemble the Jaguar E-Type that Nissan purchased as a test vehicle.

HANAKAWA Hitoshi, a Yamaha engineer, who said in a much later Japanese magazine interview, “It was the first time we had done any serious panel work, so we encountered one problem after another”. So Nissan sent their expert, but such was the lack of knowledge he found at Yamaha, that he returned the next day in disbelief. Yamaha was not about to give up, so they hired NISHIOKA Mikio. Production of the prototype was confidential; it was built in a secret room on the second mezzanine floor at Yamaha.

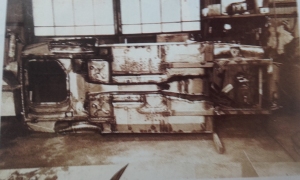

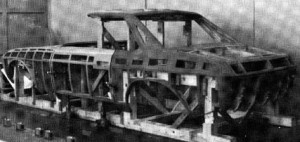

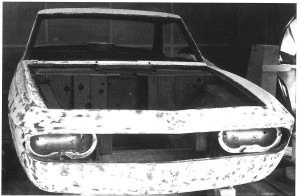

(Authors note- I am not 100% convinced that these are the Silvia prototype, but the magazine article where these photographs come from is wholly concerned with the Silvia body production at the Tonouchi plant (and I have had this human translated). Also the picture of the front nose panel (which looks very much Silvia) comes from the same source. We are used to seeing the Silvia with a ladder chassis, this looks like subframe/independent suspension. Though this was part of the overall project design brief, or is it the underpinnings of the A550X? There is no Japanese internet blog chat over this, so correct? More work needed….).

Authors note; a thought for discussion. We know the Silvia prototype was to made using the SP310 inner panels, and the design brief for the A550X was for an uni-body/monocoque. What if the photos above are correct, and this is something to do with the Silvia prototype? We know that both cars were under the same project, so there is not much of a leap to think the Silvia prototype could also have the design brief for a monocoque. Could using the SP310 platform mean the use of the inner panels and floor, but not the sp310 chassis? Was the Silvia design meant to be a monocoque, but due to such a limited time to get the prototype finished for the next Motor Show, the people in Nissan moved to mounting the body onto an existing chassis to meet the deadline? The Silvia (and to a lesser extent the SR311 -but this a continuation of the SP311 model) was the last production car to be on a separate chassis. The next selection of models were all monocoques, Datsun Sunny (Kimura san design) Datsun 510, Datsun S30 series. Could the Silvia have missed out on being more special?

NISHIOKA san was an experienced independent outside advisor who would guide Yamaha to produce a finished body in just 40 days. Yamaha also had high technical ability and the prototype was finished in 6 months, a day before the 15th October 1963 deadline set by Nissan. (As you see from the prototype, below, it looks very much like the production model to come. There are a few minor differences between them; no reverse light or wing mirrors and Perspex covers over the head lights). Great care was extended to the final prototype’s body and paint finish. The prototype was painted in a light pearl metallic colour.

The prototype was shown to Nissan executives and Nissan President, KAWAMATA Katsuji at a small test track at Nissan’s Tsurumi factory and design offices. This was the first time the President had seen the car, and he didn’t like it. The president said, “I can’t put it on the show! I (Kimura san) was told to write a production plan and proceed.” In response to this, the development for the 1964 motor show started. So with that, plans for exhibiting at the Tokyo Motor show in a few days’ time were put off. Nissan had a general rule, of only showing cars at Motor shows that were destined for public sale. The prototype CSP310 had not been given the commercial go ahead.

Despite KAWAMATA san dis-likes of the car, Yamaha finished a second Datsun 1500 coupé show car by the end of 1963 and in addition, a running prototype was built at about the same time. A left hand drive prototype was also produced, (timeline unknown) probably when production was given the go ahead for right hand drive versions and Nissan were seeing if the concept would work as LHD.

Also at some point, Kimura san also designs the Silvia emblem and logo.

To bring the csp310/Silvia to here and beyond just couldn’t happen with just KIMURA san’s initial exterior design. No doubt KIMURA san would carry on designing parts for the car. A few other names I have found (there was probably many) who were involved with the project; NAKAMURA Haruyoshi (No.2 Design Planning Dept. – chassis design section), MATSUMOTO Seijiro (PR Department), SASAKI Kenichi (No.2 Design Planning Dept. – development section), MACHIDA Toru (No.3 Design Planning Dept. – secondary equipment design). TAMURA Kumeo joined the project and would be an assistant to YOSHIDA san. A side note, both TAMURA and YOSHIDA san went on later to be part of the design team of the legendary Nissan S30 series. It looks one of workers who actually did the hands-on metal work to form the body of the production Silvia was called TSUJIGUCHI Akira. Another 3 names I have found from the Tonouchi plant (where the Silvia body was assembled) are WAKATSUKI Kunio- auditor, WADA Yojiro – management team member, KUROSAKI Motoyuki –team member.

The prototype 1500 coupé was held with high regard internally within Nissan, and a production schedule given around March 1964. Though it wasn’t a complete hit. YOTSUMOTO san says there was some criticism from some outside that the design was not Japanese and more study was needed. But from YOTSUMOTO sans point of view, as he was in command of making this car he wanted to somehow change the Japanese style.

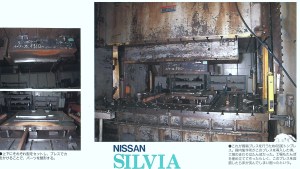

As a result from this production schedule it was decided it was not commercially viable to hand produce all the body panels by hand. So in a hurry it was decided to outsource production to Nissan’s Tonouchi Works where the panels would be fabricated using its metal press. And thus Nissan decided to produce the production model themselves. This was not received well at Yamaha, as they were originally promised the Silvia body production contract. HANAKAWA san of Yamaha collated all the drafts and original structural drawing of the design and handed them to Nissan.

Nissan exhibited the 1500 coupe at the 11th Tokyo Motor Show in October of 1964. The car was to have a 1500cc G series engine and shown with the name, Datsun 1500 coupe, the Silvia name would come later. The reason is in house at Nissan, Datsun was used for engines up to 1500cc, and Nissan brand from 1600cc on. The Silvia name was decided by the Public Relations / Promotion Department.

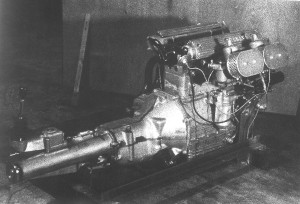

It must have been shortly after the 11th Tokyo Motor Show and prior to when production started, that the engine was swapped. Out went the G series engine (1488cc) and replaced with the R series 1600 unit (1595cc). The reason for this was the R series was much better and more refined at running at continuous higher rpms, a key factor for a sporty car. This was a modified version (inc. shorter stroke) of the H19 series found in the Nissan Cedric. This made the engine revvy, and in-keeping with its sporty car image. The gearbox was also given a swap too, using a 4 speed with a ‘Servo’ patent made under licence from Porsche. This car was Nissan’s first with this type of gearbox, which gives it a smoother change. With the change of engine the car was now called the Datsun 1600 coupe or the Nissan 1600 Coupe. To complicate matters, the name Silvia was also added, or a combination of these were used, depending on market and publication.

It would be safe to assume production started shortly after this year’s Tokyo Motor Show, as Nissan states 27 units were produced in 1964 and initially 10-15 units were produced per month (quoted from another source). Even using the metal press at the Tonouchi plant, it took time and effort to get a car and its panels made.

The metal press at Tonouchi that was used to form the panels had female and male dies which were about 20mm thick, and numerous dies were needed to make all the panels. The steel plate which would form the panels (about 1mm thick) was placed between the male and female dies and pressed. The parts could not be completed by pressing once and pressing would be needed again and again to complete one part. This was especially true of 3-dimensional panels with complicated shapes; the respective panels would be pressed many times to obtain the finished part. Panel distortion and internal stress were also removed by using the press as well. Panels were necessary assembled on a jig.

The Silvia body was assembled on a 5x3m rectangular metal plate which had legs attached to it to form a large jig. Onto this jig panels were temporarily fastened and it is said that some of the panels were hung. By doing this the whole body was temporarily assembled so that gaps and panel fit could be checked. As the panels were only lightly fixed in position, gaps and panels could be adjusted and re-assembled by hand. It could take more than 10 times mounting and removing the roof panel to get the gaps matched. Distortion of the roof was easy to accumulate, so the lining up of the roof happened carefully. The front grille, apron and front wing area was also another section of the exterior body requiring careful elaborate work. In addition to this, the Silvia does not have any body seams. These are hidden and give the Silvia body the impression of being made from one piece of sheet metal (apart from the apertures – though the bonnet sits lower than the wing tops). The exterior panels were first spot welded together. Then welded carefully at a higher temperature (to prevent distortion) and lead loading would be added to hide the seams.

The bare chassis with the engine already in place was delivered to Tonouchi Works and the finished body was bolted on. Then each Silvia was completed carefully by hand one by one.

After all this careful handmade work was done (this was the first time Nissan had produced a body with this amount of work and finery) the finished body was bolted to a bare chassis and delivered back to Nissan’s Oppama factory, to be finished. The handmade work didn’t finish there, as we know now the interior and exterior trim does not always fit another Silvia body; the likes of the interior trim has the corresponding body number written on the underside of the trim pieces.

During this movement between factories small cracks would appear at the seams, especially between the roof and the top of the C-pillar, due to the distortion and twisting here. Nissan’s most skilled craftsmen would do this advanced work to eliminate the fault at Tonouchi. Nissan would carefully inspect the body for cracks and pinholes with a magnifying glass. If any were found the vehicle would be returned to Tonouchi for paint removal and correct the fault. Since the Silvia was painted in metallic paint it was difficult to match the paint and a better technique was necessary to paint after the fault was repaired.

AOKI Hideo, a test driver / reviewer for a magazine article, wonders why the price couldn’t be 1 million Yen. As IZUMI Tomoharu says “a lot of man hours were spent on the vehicle body and finish”. With all this care going into the body work, this was pushing the purchase price up. In Japan, the Silvia was launched for sale in March 1965. The Silvia was expensive, costing 1.2 million Yen, compared to a Nissan Bluebird 1300DX (P411) costing ¥674,000 and economical cars (e.g. Corolla) being about ¥400,000. This was a luxury car and was never meant to sell in large volumes. As quoted by AOKI Hideo from a period magazine article, “rather than a mass-produced sports car, it is a bespoke car …..”

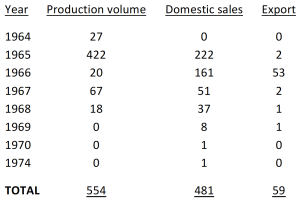

Production and sales (all RHD) from Nissan;

From the export number about 49 units went to Australia and about 10 sold to other Pacific Rim countries, e.g. Papua New Guinea got 2 that have come to light (whether these were offical imports is not known). There was 3 Silvia’s imported to a Nissan dealership in Klerksdorp, South Africa (1967/8), and a Silvia that was exported to Hawaii (though I understand it was an un-official import). The sharp eyes among you will notice the production volume has more than sales, 14 cars. As Alan Bent points out on his old Silvia website, were these sold/given to Nissan Motor Co. executives and thus not chalked up as official sales, or is there a typo somewhere? And a Silvia sold in 1970 and 1974???!!

Importation of Silvia’s to Australia didn’t start until after its launch at the 32nd Melbourne Motor Show in February 1966 (Melbourne newspaper link, below). And to begin with some of these were 1965 produced units. They were expensive too in Australia, costing $4390 compared to $1798 for the Datsun Bluebird or $4300 for a Lotus Elan.

The Silvia was never designed or produced with an export market in mind. The nearest they came was exhibiting a RHD car at the New York Motor show in March 1965, just to gauge public reaction. And anyway, the headlight position for the US market still meant formal import would not have been allowed.

For a number of years there has been speculation to whether any Silvia’s was imported to Europe, as it appears on a few Nissan Europe brochures, circa 1967, but there is no knowledge of one actually being there. To advertise a car model, but not sell it….? Recently I have been given a couple of photographs of a Silvia that had been imported in 1967 to Holland and shown under Nissan’s wing. This is quite late on in its production period and I think it was more a way of showing Europe where Nissan was at with its design thoughts. Whether this Silvia stayed in Europe or went back to Japan, this trail has just started…..

The Silvia has been looked at by some through its sales figures to guage its success, and deemed it disappointing or even a failure. Try saying that about a Italian coach-built 1960’s Ferrari road car; also being an expensive, luxury item, hand built, and with a limited target market….. And that is what it was. If Nissan wanted to build more (which I doubt), production would have been through the assembly line than hand assembling each car which is expensive and time consuming. Back to AOKI Hideo’s quote of 1965 (above), they knew where the car was being pitched in the market when the car was first sold and probably being developed.

This is backed up with words from the Nissan President, KAWAMATA Katsuji, ” a sports car is not for making profits but to act as a showcase for our company”.